The story so far

The first blog in this series was written just after an anti-corona lock-down was enforced in Bangladesh on 26th March 2020. We showed how the shock was dealt with by the 60 low-income households in central Bangladesh who volunteer as ‘diarists’ in our daily financial diary project. In the second blog we saw just how bad things got during April 2020, the first full month under lock-down. In this, the third blog in the series, we look at the partial recovery that took place in May.

Rezia (not her real name) has had an event-filled life, not least since July 2017, when we met her and started tracking her daily transactions.

Rezia (not her real name) has had an event-filled life, not least since July 2017, when we met her and started tracking her daily transactions.

Now about 35, she married at 12, and by 2018 her older son (now 19) had been married and separated. Rezia’s husband drives a battery rickshaw but appendicitis laid him low for three months in 2018, so Rezia decided to open a small hot-cake shop (pictured). Her husband disapproved of this, and their relationship deteriorated.

Rezia decided to seek work abroad. She tried for a job in Jordan, but ended up in Saudi Arabia in November 2018. It didn’t go well: she got jaundice and in February 2019 she came back. Neighbours then intervened to bring about a reconciliation with her husband, who agreed that she could try the cake shop again.

The new shop took time to set up, but she made her first sales in early November 2019.

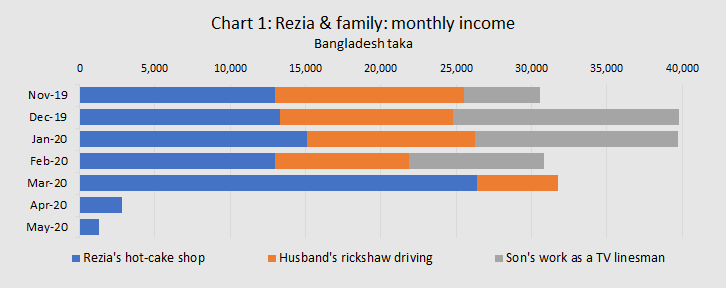

As Chart 1 shows, by the end of 2019 the family was working as a unit. Rezia is the household’s money-manager, and both her husband’s takings as a rickshaw driver and the son’s income as a TV-dish line installer were flowing into her hands. In December 2019 they earned 40,000 taka, or about $470 at market exchange rates. Things were looking up.

But in March the son’s job disappeared in a clash between two rival firms. Then the corona lock-down came into force on March 26th. As we see in the chart, things came to a sudden halt.

Rezia’s own views of the situation

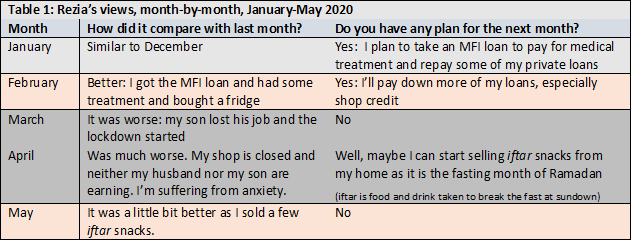

At the end of each month, we ask our diarists to tell us how the month compared to the previous month, and to tell us of any plans they have for the following month. Table 1 shows Rezia’s replies.

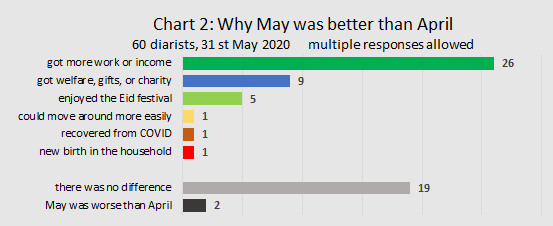

The pattern we see in Table 1 – a sharp decline in April followed by a shallow improvement in May – is similar to many of our 60 diarists. Chart 2 summarises our diarists’ views at the end of May.

How did they survive?

In the two bleakest months, April and May, Rezia’s household received no other inflow of money besides the tiny amounts she earned from her shop. They did not withdraw savings, even though she had over 19,000 taka ($225 at market exchange rates) in savings in two MFIs (from whom she also has loans outstanding). This was partly because the MFIs shut down, partly because Rezia, like many others, was reluctant to reduce her reserves in the face of so much uncertainty. They did not borrow from neighbours, though they did take goods on credit from local shopkeepers. They did not receive any gifts (even though they are evidently poor and Ramadan encourages the better off to support the poor). They did not receive any government welfare payments, nor food relief. Rezia’s is an extreme case, but the trends we report here were true of many other diarists: there was not much borrowing, very few savings withdrawals, and only limited receipt of gifts and charity, much of it in the form of food parcels given by private households, companies, political parties, and entities like school committees. The picture shows Rezia with her elder son.

In the two bleakest months, April and May, Rezia’s household received no other inflow of money besides the tiny amounts she earned from her shop. They did not withdraw savings, even though she had over 19,000 taka ($225 at market exchange rates) in savings in two MFIs (from whom she also has loans outstanding). This was partly because the MFIs shut down, partly because Rezia, like many others, was reluctant to reduce her reserves in the face of so much uncertainty. They did not borrow from neighbours, though they did take goods on credit from local shopkeepers. They did not receive any gifts (even though they are evidently poor and Ramadan encourages the better off to support the poor). They did not receive any government welfare payments, nor food relief. Rezia’s is an extreme case, but the trends we report here were true of many other diarists: there was not much borrowing, very few savings withdrawals, and only limited receipt of gifts and charity, much of it in the form of food parcels given by private households, companies, political parties, and entities like school committees. The picture shows Rezia with her elder son.

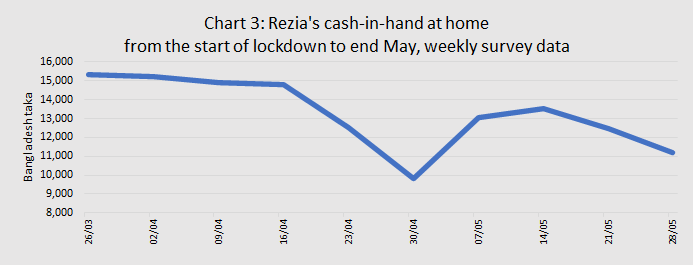

Rezia coped with the situation by old-fashioned frugality. She had about 15,000 taka ($175) at home when the lockdown was declared in late March, much of it left over from the loan of 60,000 taka from the MFI BASA that she took in February. By ‘tightening her belt’, cutting down on all but essential shopping, she preserved much of this balance, topped up in small part with her shop earnings, through to the end of May. Chart 3 shows the balance of her cash-in-hand on a weekly basis:

To understand exactly how Rezia managed this, we can compare her household’s expenditure during the crisis with pre-crisis levels. We do that in Chart 4.

Even in good months, Rezia spent more than most diarists on food, as she focused on paying off debt and growing her business. But what stands out in Chart 4 is the month of April, where Rezia spent only on food. Then in May we see her food bill rise, as she buys kerosene and sets up her home-based iftar offerings. Rezia’s business is not yet big enough for her income to revive, but many other diarists have seen their income pick up in May, as Chart 5 shows.

A false dawn?

On May 25th Bangladesh celebrated Eid al Fitra, the feast that marks the end of the holy fasting month of Ramadan. Some days before, the government had let it be known that the lock-down was about to be eased, even lifted entirely. Our diarists had mixed feelings about that, as we found when we ran a survey among them in mid-May. As Chart 6 shows, the majority were against the relaxation of the lock-down, mostly out of fear of the disease.

Rezia was among the minority of women who were in favour of the relaxation, on the grounds that it would enable her to restart her business. The government appears to have agreed with her, for on 31st May the lock-down was fully lifted. Since then the daily total of confirmed infections has soared. The balancing game that pits public health against the economy is being daringly played in Bangladesh. Next month another blog in this series will report on our diarists’ welfare in June.

Stuart Rutherford

June 4th 2020

All fieldwork for the Hrishipara Daily Diaries Project is now being funded by L-IFT. We gratefully acknowledge their invaluable support.

This first appeared on the Global Development Institute blog http://blog.gdi.manchester.ac.