The current pandemic has forced many countries to be put under strict lock-down. This will hopefully avoid the disease to spread in the country or at least to reduce the pressure on the fragile health systems, especially in less developed countries. However, this could have a counter effect of increased suffering due to reduced means of living during this lock-down. The choice for health over livelihood may have even deeper impact on vulnerable groups like the refugees.

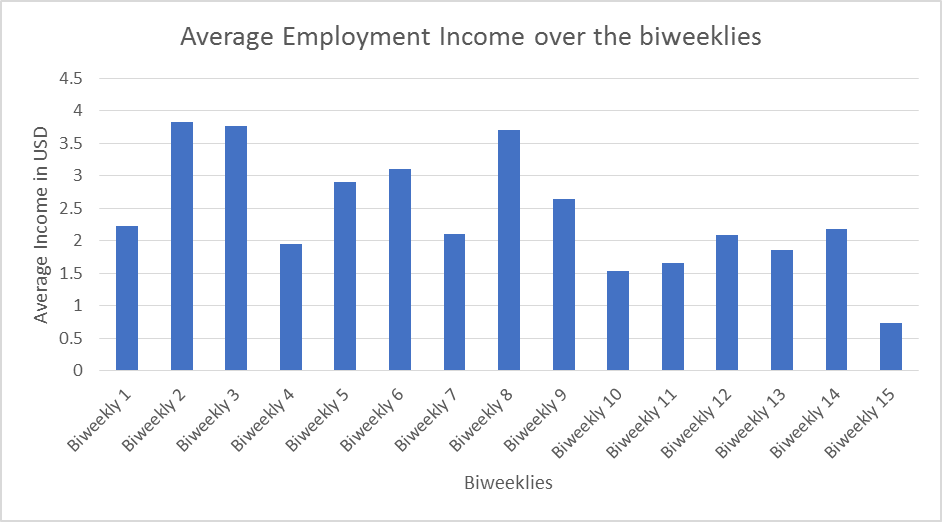

In our refugees’ diaries study in Uganda, we see clear effects on livelihood since the lock-down has been in place. Every biweekly interview, the respondents in Nakivale and Kiryandongo refugee camps are asked the amount of income they earned from employment, business and agricultural activities in the previous two weeks. This article assesses employment income over the interviews. The lock-down commenced on 30th March, but was announced a little earlier. Interview biweekly 14 started a week before lock-down and ended a week after lock-down.

Employment income includes income from working on other households’ farms; casual labour; working in small business; working in formal business; working for authorities in the camp; working for NGO; commission work; community organizations (CBOs) and apprentice.

In general 46 percent earn their income through some form of employment. Out of these, about 18 percent work on other farms household according to the baseline survey. The income earned from this has flattened in the last few biweeklies.

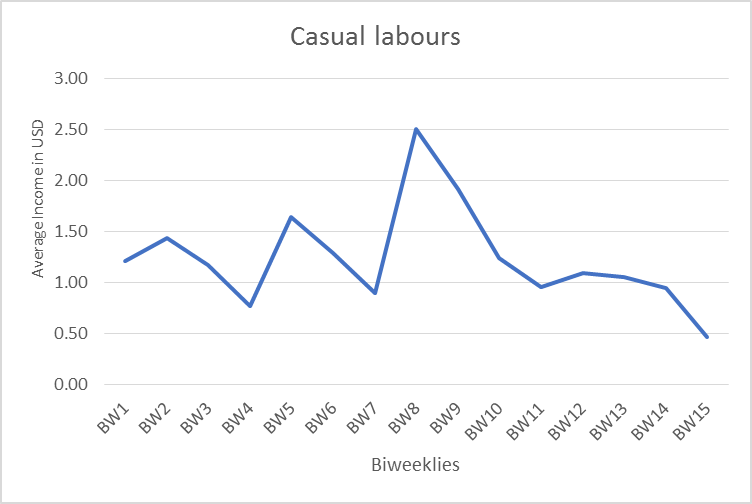

Earning from casual labour has also plummeted. In the baseline interview, 22 percent have indicated this as a form of employment with which they support their livelihood. It has decreased by 56 percent from biweekly 13 to biweekly 15.

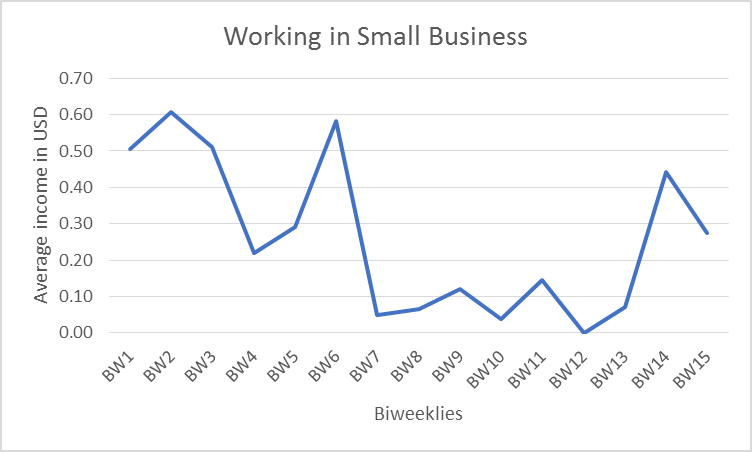

“Working in small business” was one of the main forms of employment to make a living (14 percent of respondents from the baseline). This displays a different pattern. It had actually increased in interview BW-14 and declined only marginally for BW-15. Most small businesses in Nakivale and Kiryandongo are ‘retail’. It may be that small businesses employed more people at the start of the lock-down and early on in the lock-down to address increased shopping for food and other essentials.

Overall, there is a decline in total employment income by more than 60 percent in the last biweekly interview. So the decline was not immediate after lock-down, but took a week to set in.

We will continuously monitor the respondents’ livelihood status over the coming weeks. In the next article, we will show the three-week impact of the lock-down on businesses.

By: Mahlet Alemayehu

This blog is written using data from the RISE project, funded by Opportunity International, with consulting services from PHB.

PHB collaborates with international development agencies, banks, regulators and other impact makers around the world to assess, implement and scale digital interventions. We leverage the expertise of our team to support the design of digital finance ecosystems that can strengthen the resilience of communities in need. To learn more about PHB activities, publications and training, visit www.phbdevelopment.com