Following on from David Hulme’s blog post Do you want to know how poor people really manage their money? Stuart Rutherford, an Honorary Research Fellow at the Global Development Institute, analyses the latest data from his fascinating financial diaries project.

The ongoing Hrishipara Daily Diary project collects data on the daily money flows of 50 low-income households living near a market town in central Bangladesh. Data collection started in May 2015 and we have published an ‘Interim Report’ covering some findings from the period up to the end of March 2016. In this blog we use more recent data to look at poor households’ savings patterns.

How poor are our ‘diarists’?

Using household net income as a measuring stick, we have categorized our 50 ‘diarists’ into four groups. The poorest have incomes which fall below the Bangladesh government’s ‘lower poverty line’ and we refer to them as extreme poor. Fifteen diarists (or about third of all diarists) are in this group. Another 7 diarists fall below the ‘upper poverty line’ and we call them very poor. Twelve more, our moderate poor diarists, have incomes up to double the upper poverty line and the remaining 16 enjoy higher incomes and we describe them as near poor. (The income figures include the value of produce farmed by diarists for their own consumption). The median income is 81 Bangladesh taka a day per person in the household, the Purchasing Power Parity equivalent of fractionally over US$2, not far from the World Bank’s ‘extreme poverty’ benchmark of $1.90.

Savings balances and savings flows

In the Interim Report we wrote about the savings and loan balances that our diarists hold in formal accounts at banks, insurance companies and MFIs (microfinance institutions like Grameen Bank, BRAC and ASA). What we found may surprise some readers. For example, we found that although MFIs were set up originally to lend to ‘the poorest of the poor’, in our sample the very poorest were the least likely to be using MFIs and in general the higher your income the more likely it was that you used MFIs. We also found that poor diarists who did use MFIs tended to use them more for saving than for borrowing. Overall, among all the diarists, savings balances were higher than loan balances. We concluded that it looked as if the MFIs have become the main receptacle for storing the savings deposits of a very large swathe of rural Bangladeshis, from the poor to the near-poor.

This analysis left many questions unanswered. Are diarists saving at other institutions besides banks and MFIs? What are their savings ‘habits’ – little-and-often or in occasional bursts, or seasonal? – and do these habits vary according to income level, or occupation, or some other characteristic? Who most likes to save? – we know that richer people tend to have bigger savings balances, but are they bigger relative to their income? And why do our diarists save?

Many of these questions are best researched by looking at the flows of income, expenditure, saving and borrowing, rather than looking at totals or balances. A strength of the financial diary methodology is that it reveals these flows in great detail and sets them in the context of the household’s economic, financial, social and even emotional life.

Going with the flow

To look more closely at savings flows, we take a sample of 44 of our diarists for whom we have complete transaction data for the six months from March to August 2016 (we have excluded six diarists for various reasons, such as their sending most of their earnings back to villages where we can’t tell how much of it was saved).

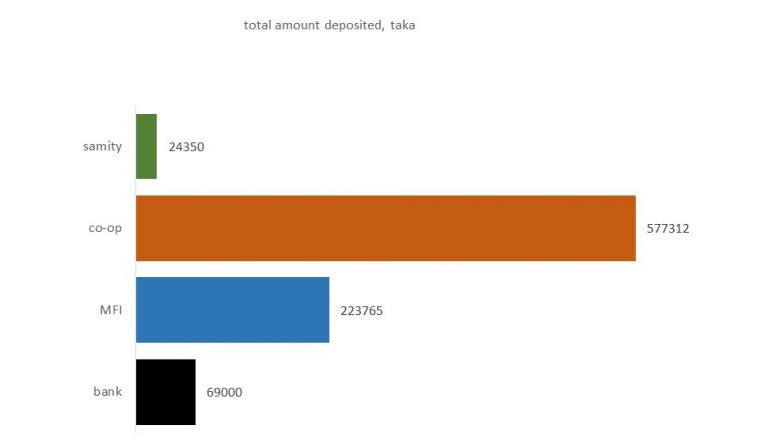

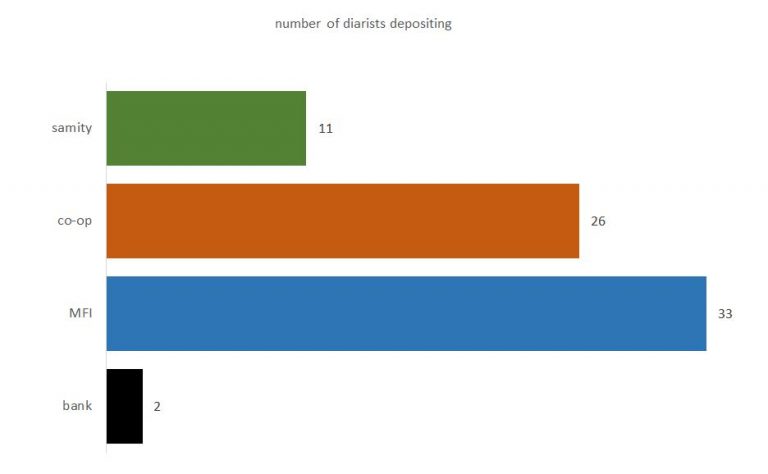

Records for these 44 diarists reveal two other popular places to deposit money besides formal banks and MFIs: the less formal local Co-operatives, and the informal village or occupational savings clubs, known in Bangladesh as ‘samities’. As the following graphics show, 40 of these 44 diarists deposited savings into one or more of these four options during the period.

More diarists deposited into MFIs than in to any other destination, but the less formal Co-operatives came a close second, and the total amount deposited into these Co-operatives during the period was greater than any of the other options. Banks attracted only two depositors, and though a quarter of all diarists in the sample saved into informal samities, the amount they saved was small.

Our diary records help to interpret these numbers. Generally speaking, the MFIs accept deposits only once a week, at a fixed time. The Co-operatives, on the other hand, take deposits at much more frequent intervals, and some send a collector each day to their clients’ homes or workplaces. Several of the samities take savings daily, but, being small entities based on the trust formed in a small community, they prefer not to handle large sums of money. All this suggests that being big enough to handle large sums, while at the same time nimble enough to collect deposits frequently, results in the most intensive saving.

Do savings rates vary with income?

The next graphic shows the saving rates (the proportion of total income deposited into the four destinations noted above) for the six-month period 1 March to 31 August 2016, by selected income class (we have omitted the very poor class because the sample size is small).

What stands out is that our extreme poor diarists, despite their income poverty, save about the same proportion of their income as do the much better-off near poor.

Within these categories, though, the behaviour of individuals varies. Our last graphic shows the percentages of total income saved by the 12 extreme poor diarists in this sample. The poorest of all (on the extreme left of the graphic) is an illiterate widow who does odd jobs for market shopkeepers for a living and feeds herself and, for part of the time, her teenage daughter on an income of less than 75 cents (PPP) a day. By avoiding debt, by living extremely modestly, and by being determined, she manages to save 25 cents most days into a Co-operative and in that way saved one fifth of her total income during the period.

Why does she do it? She tells us she isn’t saving for a particular expenditure, but to protect herself from illness, old age and misfortune, and to provide a better life for her daughter – including as a good a marriage as she can arrange for her. Such reasons for savings are the most commonly heard among our poorer diarists.

These brief notes suggest that the propensity to save is common to all levels of poor households, but the rate of savings depends on a mix of factors: the savings opportunities that are available, the way in which savings is collected, and the specific circumstances and personality of the saver. Financial diaries are perhaps the best way to explore these issues in great detail.

Any reader who would like to grapple with the Hrishipara data can get them from the author at write.ser@gmail.com.

This first appeared on the Global Development Institute blog http://blog.gdi.manchester.ac.